EDINBURGH, Scotland — Even cave-dwellers were fascinated with the mysteries of time and outer space. Analysis of some of the world’s oldest cave paintings revealed that ancient people had a better conception of time and astronomical properties than previously thought.

A study led by researchers at the University of Edinburgh found that perhaps as far back as 40,000 years ago, humans were already keeping track of time using their knowledge of how the positions of stars and constellations in the night sky shift over millennia.

The UE researchers, joined by others from the University of Kent, studied Neolithic and Paleolithic paintings in France, Turkey, Spain, and Germany. All of the paintings they studied showed signs of this ancient method of time-keeping.

Most of the recovered prehistoric cave paintings still surviving today depict humans and animals. It was thought that the animals were simply representations of wild game and predators that early humans dealt with in their everyday lives, but the new analysis suggests that the animals in these paintings are actually representations of constellations in the sky, used to mark dates and events, such as comet strikes.

For example, the researchers interpreted a stone carving at the dig site Gobekli Tepe in Turkey to be a memorial for those lost in a comet strike around 11,000 BC. This comet strike is thought to have initiated a mini-ice age.

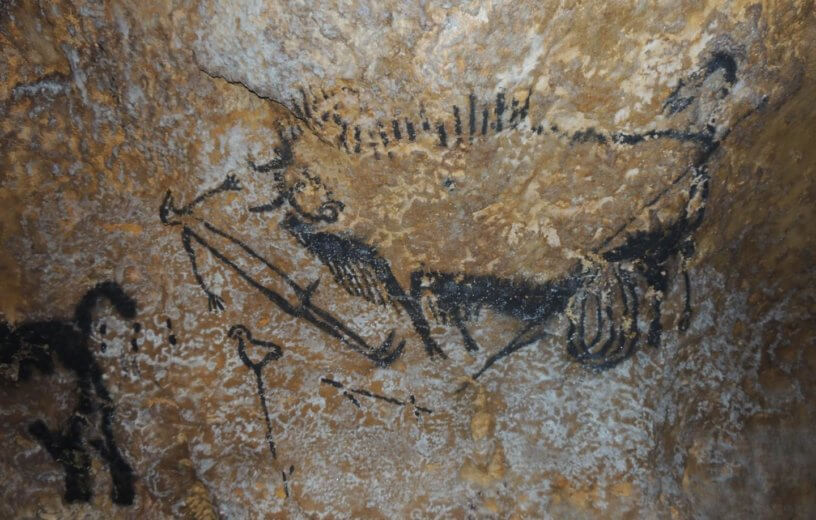

The team also studied one of the most famous ancient paintings, the Lascaux Shaft Scene in France. The painting features a dying man and animals strewn above him. The researchers decoded the painting using a chemical dating process on the paints and compared the data to where certain constellations were in the sky at the time using predictive computer software. They found the scene, believe to have been created in 15,200 BC, seemed to have commemorated another comet strike.

Similarly, the oldest known sculpture, the Lion-Man of Hohlenstein-Stadel Cave (38,000 BC) shows that its creator followed this primitive time-keeping system.

“Early cave art shows that people had advanced knowledge of the night sky within the last ice age. Intellectually, they were hardly any different to us today,” explains UE researcher Dr. Martin Sweatman in a media release. “These findings support a theory of multiple comet impacts over the course of human development, and will probably revolutionize how prehistoric populations are seen.”

The authors also suggest that the paintings show ancient humans recognized the effect of shifts to the Earth’s rotational axis, also known as precession of the equinoxes, which had been credited to the ancient Greeks. This new analysis suggests that around the time the Neanderthals went extinct — before humans had colonized Western Europe — people could define dates to within 250 years using their knowledge of how the stars shifted in position above them.

The study was published November 2, 2018 in the Athens Journal of History.