MANSOURA, Egypt — Fossil remains of an ancient, four-legged whale species that swam the oceans 43 million years ago has been discovered in the Sahara Desert. Scientists say the prehistoric finding is a “critical” piece of history behind the evolution of whales today.

Fragments of the skeleton of the beast reveal it had a long snout, sharp, pointed teeth, and powerful jaws. Considered the killer whale of its day, it looked like a cross between a dolphin and a giant aquatic wolf, experts say. It likely reached up to 10-feet in length and weighed nearly a ton. The newly-found species existed during the middle of the Eocene period and is named Phiomicetus anubis after the canine-headed Egyptian god Anubis. In Egyptian mythology, Anubis has a dog’s head and a human body. The god was associated with mummification and the afterlife.

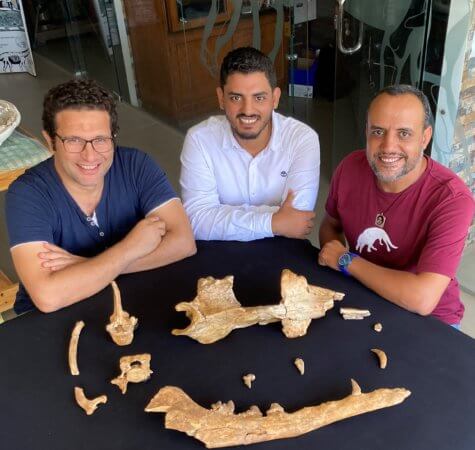

“When the anatomical evidence led us to the conclusion that it is a new species of whale, it was an amazing sensation of joy and enthusiasm,” lead author Abdullah Gohar, a graduate student at Mansoura University in Egypt and researcher with Sallam Lab, tells StudyFinds.

Researchers say the whale ambushed large prey including rays, sharks, and sawfish, as well as marine reptiles by trapping them in shallows near the shore. The exciting discovery sheds fresh light on how the enigmatic mammals eventually moved from land to water.

Phiomicetus was a member of the earliest whales, or protocetids, that gave rise to the biggest animals that ever lived. Today’s blue whales reach 110 feet and weigh as much as 190 tons — two and a half times more than the largest dinosaurs. “The species was clearly preying upon large-bodied prey like a killer whale,” explains Gohar. “Compared with earlier whales, it has a more elongated temporal fossa, larger third lower incisor, and longer articulation area between the mandibles. These adaptations indicate an animal that was a more successful predator than its relatives.

“Phiomicetus further shows that the protocetid whales had already diversified in their anatomy and feeding behavior, more than was previously thought,” Gohar adds, “showing a capacity for more efficient oral processing of prey items than the normal protocetid condition, thereby allowing for a strong ‘raptorial’ feeding style.”

It would have bitten or snapped its prey in half, swallowing it in big chunks without chewing.

The unearthed fossilized remains include the skull, ribs, and other parts of the skeleton. They were dug up during an international expedition to the Fayum Depression, an animal graveyard near the Nile Valley, in 2008. The great desert was “born” about seven million years ago and had been covered by a vast sea called Tethys.

Whales evolved over 50 million years ago and started out as a terrestrial creature. They were typical land animals with long skulls and large, carnivorous teeth. In recent years, insights from fossils have added details to their history. But the big picture of their emergence in Africa has remained a mystery. Phiomicetus is the most primitive whale known from Africa, filling a vital piece in the jigsaw.

“Even more importantly, this contribution significantly advances understanding of the role that the African waters played in whale evolution during the Eocene,” says Gohar.

“It is tempting to think transitional species are always going to be transitional in terms of their adaptations. But in reality, they are often specialized for something. Phiomicetus highlights an early adaptation for feeding on large prey very shortly after its fish-eating ancestors became fully marine,” adds Dr. Robert Boessenecker of the College of Charleston, a study co-author, in a statement.

Sallam Lab is the research group led by professor Hesham Sallam. It is dedicated to educating Egyptian vertebrate paleontologists, expanding awareness of Egypt’s vertebrate paleontological resources, and undertaking collection, preparation, study and curation of Egypt’s fossil vertebrates.

The study is published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.