GENEVA, Switzerland — Exposure to the cold can treat autoimmune diseases as the body “stops fighting itself” in order to maintain heat, a new study reveals.

Researchers in Switzerland believe that staying in low temperatures could be a new way to treat multiple sclerosis (MS), type 1 diabetes, lupus, and other diseases that involve the immune system attacking the body’s own tissue. According to the National Institutes of Health, 23.5 million Americans deal with one of the over 80 autoimmune diseases known to scientists.

The new study examined mice suffering from a disease model based on human multiple sclerosis that they placed in a colder living environment – about 50°F. The research team deciphered how exposure to cold pushed the animals to divert their resources from the immune system towards maintaining body heat. As a result, the immune system vastly decreased its harmful activity which limited the attack on the autoimmune disease.

Changing the body’s priorities

“The defense mechanisms of our body against the hostile environment are energetically expensive and can be constrained by trade-offs when several of those are activated,” Professor Mirko Trajkovski from the University of Geneva says in a release. “The organism may therefore have to prioritize resource allocation into different defense programs depending on their survival values.”

“We hypothesized that this can be of particular interest for autoimmunity, where introducing an additional energy-costly program may result in milder immune response and disease outcome. In other words, could we divert the energy expended by the body when the immune system goes awry?” Trajkovski continues.

“We show that cold modulates the activity of inflammatory monocytes by decreasing their antigen presenting capacity, which rendered the T cells, a cell type with critical role in autoimmunity, less activated.”

Keeping the immune system from focusing on self-harm

Researchers say that by forcing the body to increase its metabolism to keep body heat up, the cold takes away resources the malfunctioning immune system would typically use to attack healthy tissue. This leads to a decrease in harmful immune cells and therefore relieves symptoms of the autoimmune disease.

“While the concept of prioritizing the thermogenic over the immune response is evidently protective against autoimmunity, it is worth noting that cold exposure increases susceptibility to certain infections,” Prof. Trajkovski adds. “Thus, our work could be relevant not only for neuroinflammation, but also other immune-mediated or infectious diseases, which warrants further investigation.”

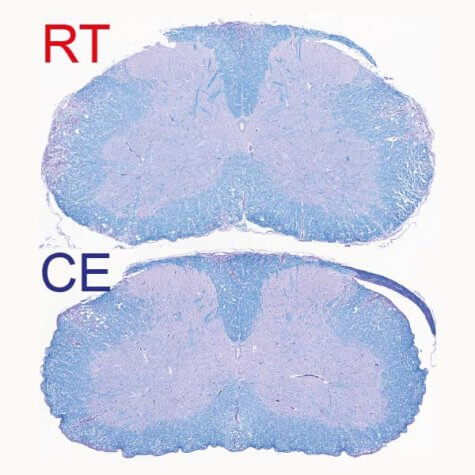

“After a few days, we observed a clear improvement in the clinical severity of the disease as well as in the extent of demyelination observed in the central nervous system,” Professor Doron Merkler says.

“The animals did not have any difficulty in maintaining their body temperature at a normal level, but, singularly, the symptoms of locomotor impairments dramatically decreased, from not being able to walk on their hind paws to only a slight paralysis of the tail.”

“While this increase is undoubtedly multifactorial, the fact that we have an abundance of energy resources at our disposal may play an important but as yet poorly understood role in autoimmune disease development,” Merkler concludes.

The findings appear in the journal Cell Metabolism.

South West News Service writer Joe Morgan contributed to this report.