BERLIN, Germany — Throughout the coronavirus pandemic, the fear has been COVID-19 reaching a patient’s respiratory system and damaging the lungs. A new study finds the virus can also enter a person’s brain through their nose.

Researchers in Germany say this explains symptoms including loss of smell and taste, headaches, fatigue, nausea, and dizziness. In some the disease can even result in stroke or other serious neurological conditions. The findings could lead to earlier diagnosis and better prevention methods, scientists say. The results come from brain autopsies of nearly three dozen patients who died from coronavirus.

The study tracked the deadly infection to the olfactory mucosa, a mucus-secreting membrane in the upper reaches of the nose. It contains cells responsible for initiating smelling sensations and is the “port-of-entry.”

Coronavirus ‘moves from nerve cell to nerve cell to reach brain’

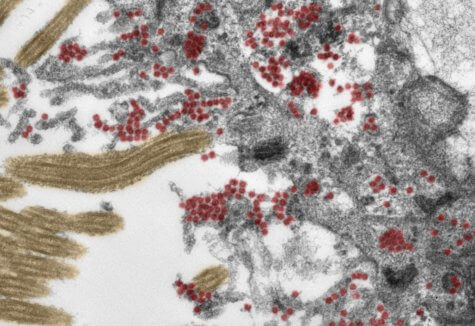

Recent studies have discovered COVID-19 in grey matter and cerebrospinal fluid, but it’s been unclear how it got in there and spread. The German team examined the nasopharynx, the upper part of the throat that connects to the nasal cavity. Researchers used the brains of 33 people with an average age of 72, including 22 men. Each person died roughly a month after the onset of symptoms.

“These data support the notion that SARS-CoV-2 is able to use the olfactory mucosa as a port of entry into the brain,” lead author Professor Frank Heppner of Charité – University Hospital Berlin says in a university release.

The discovery was also supported by the close anatomical proximity of mucosal cells, blood vessels and nerve cells in the area.

“Once inside the olfactory mucosa, the virus appears to use neuroanatomical connections, such as the olfactory nerve, in order to reach the brain,” the neuropathologist adds. “It is important to emphasize, however, that the COVID-19 patients involved in this study had what would be defined as severe disease, belonging to that small group of patients in whom the disease proves fatal. It is not necessarily possible, therefore, to transfer the results of our study to cases with mild or moderate disease.”

The manner in which the virus moves on from the nerve cells remains to be fully explained.

“Our data suggest that the virus moves from nerve cell to nerve cell in order to reach the brain,” co-author Dr. Helena Radbruch says. “It is likely, however, that the virus is also transported via the blood vessels, as evidence of the virus was also found in the walls of blood vessels in the brain.”

Another dangerous virus attacking the brain

COVID-19 is far from the only virus capable of reaching the brain via certain routes. The team points out this is also a characteristic of rabies and herpes. The study, published in Nature Neuroscience, also detected immune cells in the cerebral fluid.

In some cases, researchers discovered tissue damage caused by stroke as a result of a blood clot.

“In our eyes, the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in nerve cells of the olfactory mucosa provides good explanation for the neurologic symptoms found in COVID-19 patients, such as a loss of the sense of smell or taste,” Prof. Heppner explains.

“We also found SARS-CoV-2 in areas of the brain which control vital functions, such as breathing. It cannot be ruled out that, in patients with severe COVID-19, presence of the virus in these areas of the brain will have an exacerbating impact on respiratory function, adding to breathing problems due to SARS-CoV-2 infection of the lungs. Similar problems might arise in relation to cardiovascular function.”

Further post mortem studies are needed to identify the precise mechanisms that control the virus’ entry into the brain. Prof. Heppner and his colleagues say the study would not have been possible without the consent of the patients’ families. They add they’re “immensely grateful” to them.

SWNS writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.