HAIFA, Israel — Archaeologists have discovered what’s believed to be proof of the oldest beer brewing operation known to man — perhaps by as many as 5,000 years from the earliest known evidence.

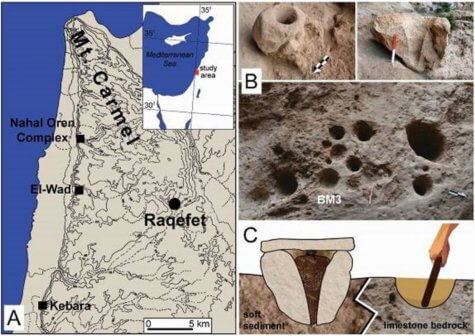

Researchers from Stanford University and the University of Haifa in Israel analyzed three stone mortars, approximately 13,000 years old, pulled from an ancient burial ground within the Raqefet Cave near Haifa. The cave was used as a graveyard for the Natufians, a group of hunter-gatherers who may very well now be known as the mothers and fathers of beer. The archaeologists say the mortars were used by the Natufians to help brew wheat and barley and store the resulting malts.

“This accounts for the oldest record of man-made alcohol in the world,” notes Dr. Li Liu, a professor of Chinese archaeology at Stanford who led the research, in a university release.

Liu says the team was surprised upon realizing the significance of the mortars. “We did not set out to find alcohol in the stone mortars, but just wanted to investigate what plant foods people may have consumed because very little data was available in the archaeological record,” she explains.

Researchers say the Natufians lived in the Eastern Mediterranean between the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods after the last Ice Age. Residue found on the mortars were identified as starch and microscopic plant particles known as phytolith, typically found when wheat and barley is malted in the beer-making process. For the Natufians, beer was believed to be a key part of the culture’s ritual feasts meant to honor the dead.

“This discovery indicates that making alcohol was not necessarily a result of agricultural surplus production, but it was developed for ritual purposes and spiritual needs, at least to some extent, prior to agriculture,” adds Liu.

In fact, the discovery may even prove that beer could have existed before bread, believe it or not. The earliest evidence of bread was also recently found from a Natufian site in Jordan, with scientists estimating the remains to be about 11,600 to 14,600 years old. Liu says the ancient beer finding is believed to be 11,700 to 13,700 years old.

Don’t be mistaken, though — the suds our ancestors consumed weren’t like the flavorful concoctions you’ll find at your local craft brewery. Instead, researchers say the cereal-based booze likely had the consistency of porridge. To be sure, Liu and co-author Jiajing Wang, a doctoral student in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures at Stanford, attempted to follow the same process they believe the Natufians used for brewing. That meant turning the wheat or barley grains into malt, mashing or heating the malt, and then leaving it to ferment with airborne wild yeast.

The authors say the particles found in the residue on the mortars were similar to the resulting residue from their trials in recreating the Natufian beer process.

“Alcohol making and food storage were among the major technological innovations that eventually led to the development of civilizations in the world, and archaeological science is a powerful means to help reveal their origins and decode their contents,” says Liu, in a statement. “We are excited to have the opportunity to present our findings, which shed new light on a deeper history of human society.”

The full study is published in the October 2018 edition of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.