BRISTOL, United Kingdom — A mysterious microscopic creature with no anus is no longer part of humanity’s family tree. Researchers have found that this fossil, which resembles the popular characters from the “Minions” movies is actually part of a different evolutionary tree.

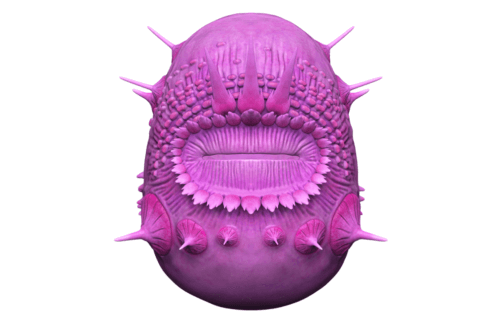

The international team describes the Saccorhytus as a “spikey, wrinkly sack, with a large mouth surrounded by spines and holes.” Researchers believed the holes may have been pores for gills — a primitive feature of the deuterostome group, which our human ancestors also emerged from.

However, an analysis of the 500-million-year-old fossil in China reveals that the holes are actually the bases of spines which broke off during fossilization. The revelation is finally clearing up the evolutionary links of the Saccorhytus.

“Some of the fossils are so perfectly preserved that they look almost alive,” says Yunhuan Liu, a professor of paleobiology at Chang’an University, in a media release. “Saccorhytus was a curious beast, with a mouth but no anus, and rings of complex spines around its mouth.”

Uncovering the true story of the Saccorhytus

Researchers say the true lineage of this creature lies in its microscopic internal and external features. They took hundreds of X-ray images at slightly different angles to create a detailed model of the fossil.

“Fossils can be quite difficult to interpret and Saccorhytus is no exception. We had to use a synchrotron, a type of particle accelerator, as the basis for our analysis of the fossils. The synchrotron provides very intense X-Rays that can be used to take detailed images of the fossils. We took hundreds of X-Ray images at slightly different angles and used a supercomputer to create a 3D digital model of the fossils, which reveals the tiny features of its internal and external structures,” says researcher Emily Carlisle from the University of Bristol.

The study found that the pores around the mouth were closed by another body layer, creating the mouth spines.

“We believe these would have helped Saccorhytus capture and process its prey,” suggests Huaqiao Zhang from the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology.

The review concludes that Saccorhytus is actually an ecdysoszoan, a group which includes arthropods and nematodes.

“We considered lots of alternative groups that Saccorhytus might be related to, including the corals, anemones and jellyfish which also have a mouth but no anus,” says Prof. Philip Donoghue of University of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences. “To resolve the problem our computational analysis compared the anatomy of Saccorhytus with all other living groups of animals, concluding a relationship with the arthropods and their kin, the group to which insects, crabs and roundworms belong.”

What happened to Saccorhytus’ anus?

Researchers say the creatures lack of an anus is pretty intriguing. Although the immediate question would be how did Saccorhytus get rid of digestive waste (possibly through its mouth), study authors explain that understanding what happened to the fossil’s anus is an important part of evolutionary biology.

Knowing how a species’ anus develops — and sometimes disappears — helps scientists understand how creatures evolve. Since the study shifts the Saccorhytus from the deuterosome to ecdysozoan group, the change removes a disappearing anus from the historical features of this human family tree. Simply put, our earliest ancestors did not see their digestion patterns change through the loss of their anus — like the Saccorhytus’ new descendants.

“This is a really unexpected result because the arthropod group have a through-gut, extending from mouth to anus. Saccorhytus’s membership of the group indicates that it has regressed in evolutionary terms, dispensing with the anus its ancestors would have inherited,” says Shuhai Xiao from Virgina Tech. “We still don’t know the precise position of Saccorhytus within the tree of life but it may reflect the ancestral condition from which all members of this diverse group evolved.”

The findings are published in the journal Nature.