Scientists boast more durable, reliable form of wearable tech as drawn-on-skin circuitry applies to skin like ‘ink on paper.’

HOUSTON — For many us, our smartwatches, smartphones, and computers may as well be bodily appendages. Now, researchers at the University of Houston have developed a way to, quite literally, attach electronics to patients’ skin. The innovative technology, featuring multifunctional circuits and sensors, are simply drawn on one’s skin using a pen.

While the idea of having circuitry bonded to one’s skin sounds like the plot of a Star Trek episode, the researchers say their invention facilitates more precise collection of health data. Moreover, while a more traditional, wearable sensor tends to collect inaccurate data when the wearer starts to move vigorously, these sensors are much more durable.

For example, imagine a heart patient wears a sensor that keeps track of their heart functioning, temperature, and other health measurements for a week or so. If those measurements are even slightly inaccurate, it could have a big impact on the treatmen a doctor chooses moving forward.

Simply put, ensuring that biological health data devices are functioning accurately is very important. This is where the skin electronics come into play; more so than any watch or wearable device, these drawn-on electronics are capable of precise data collection no matter what type of activity an individual is engaged in.

Additionally, these drawn-on-skin devices don’t require expensive or burdensome equipment, and can be drawn-on quite easily.

CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER & GET THE LATEST STUDIES FROM STUDYFINDS.ORG BY EMAIL!

“It is applied like you would use a pen to write on a piece of paper,” says Cunjiang Yu, Bill D. Cook Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Houston, in a release. “We prepare several electronic materials and then use pens to dispense them. Coming out, it is liquid. But like ink on paper, it dries very quickly.”

Wearable bioelectronics, more specifically soft patches that adhere to the skin, are emerging as a helpful way to monitor, diagnose, and treat various health problems. However, even these devices face various problems that arise when the patch doesn’t move completely in-sync with the wearer’s skin.

Meanwhile, drawn-on skin electronics allow for customization to measure or collect specific types of health data. Researchers believe these devices may prove invaluable in situations where it’s hard to find stocked medical equipment, such as battlefields.

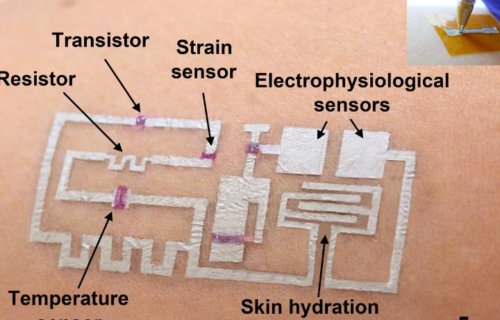

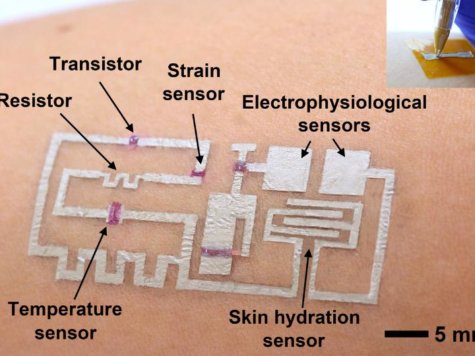

Muscle signals, heart rate, temperature, and skin hydration are just a few examples of the physical data these devices monitor. In some cases, these electronics even show the ability to speed up the wound-healing process.

Each drawn-on skin device consists of three inks: conductor, semiconductor and dielectric.

“Electronic inks, including conductors, semiconductors, and dielectrics, are drawn on-demand in a freeform manner to develop devices, such as transistors, strain sensors, temperature sensors, heaters, skin hydration sensors, and electrophysiological sensors,” the study concludes.

The study is published in Nature Communications.

Like studies? Follow us on Facebook!