PARIS, France — Before there were war horses, a new study finds ancient humans bred hybrid donkeys specifically for battle thousands of years ago.

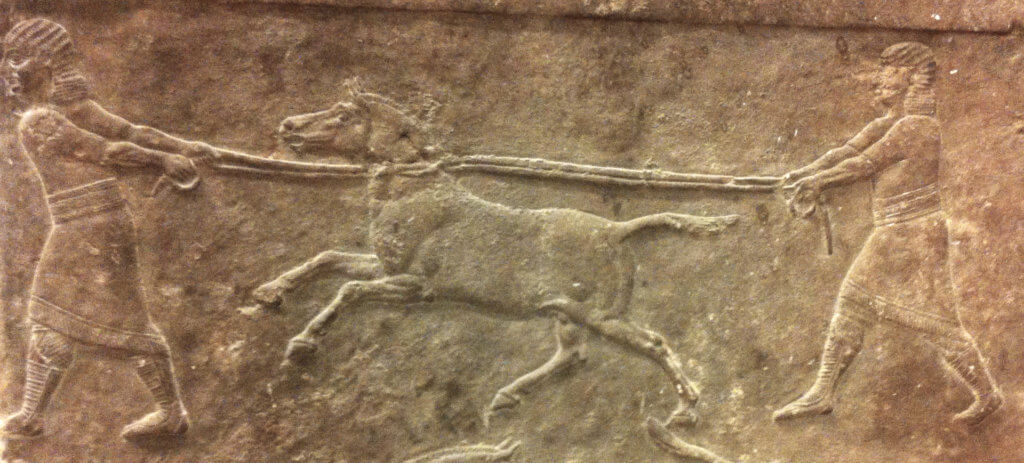

The beasts, called “kungas,” were stronger and faster than normal donkeys. They were also much quicker than horses, according to scientists in France, who believe they were the first ever animal hybrids. Texts and carvings from ancient Mesopotamia, dating back 4,500 years, show that the elite used pack animals for travel and warfare.

However, the nature of those animals remained mysterious until now. French researchers used ancient DNA to show that the animals were the result of crossing domestic donkeys with wild asses.

Researchers add this makes them the oldest known example of animal hybrids, produced by Syro-Mesopotamian societies 500 years before the arrival of domestic horses in the region.

“Equids have played a key role in the evolution of warfare throughout history,” the team from of the Institut Jacques Monod (CNRS) writes in a media release.

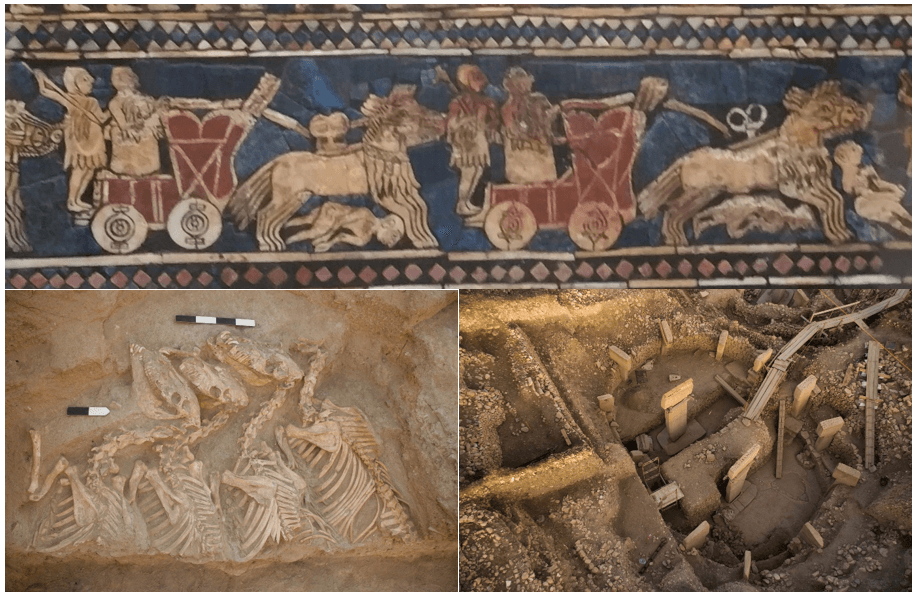

“Although domesticated horses did not appear in the Fertile Crescent until about 4,000 years ago, the Sumerians had already been using equid-drawn four-wheeled war wagons on the battlefield for centuries, as evidenced by the famous ‘Standard of Ur’ – a 4,500-year-old Sumerian mosaic.”

Study authors say cuneiform clay tablets from this era mention “prestigious” and extremely valuable equids called “kungas.” Until now, scientists have debated what kind of animals the kungas were.

‘Super donkeys’ received special burials

Paleo-geneticists addressed this question by studying the equid genomes from the 4,500-year-old princely burial complex of Umm el-Marra, in present day northern Syria. An American archaeozoologist first proposed that these animals, buried in separate installations, were the kungas.

“Although degraded, the genome of these animals could be compared to those of other equids: horses, domestic donkeys and wild asses of the hemione family, specially sequenced for this study,” the study authors report.

The remains include an 11,000-year-old equid from the oldest known temple, Göbekli Tepe, south-east of present-day Turkey, and the last specimens of Syrian wild asses — who went extinct in the early 20th Century.

“According to the analyses, the equids of Umm el-Marra are first generation hybrids resulting from the cross of a domestic donkey and a male hemione,” the researchers explain.

Since kungas were sterile and the hemiones were wild, the team says ancient humans crossed a domestic female with a previously captured hemione each time to produce a hybrid.

Bottom, left: Equid burial from Umm el-Marra, Syria. (© Glenn Schwartz / Johns Hopkins University.)

Bottom, right: Enclosure D with T-shaped pillars at Göbekli Tepe, Turkey. (© German Archaeological Institute, Berlin (Germany))

Easy-to-breed horses marked the end of the ‘kungas’

Instead of domesticating wild horses in the region, it appears the Sumerians produced and used hybrids, combining the qualities of the two distinct parent donkeys to create offspring that were stronger and faster than donkeys, but more controllable than hemiones.

“These kungas were eventually supplanted by the arrival of the domestic horse, which was easier to reproduce, when it was imported to the region from the Pontic Steppe,” the team concludes.

The findings are published in the journal Science Advances.

South West News Service writer Stephen Beech contributed to this report.