CAMBRIDGE, England — Invasive species “hitching” rides on tourist and research ships are threatening Antarctica’s native wildlife, warns new research. With the potential to arrive from almost anywhere in the world, scientists say the invaders pose a serious threat to the continent’s unique ecosystems.

New research led by the University of Cambridge and the British Antarctic Survey has tracked the global movements of all the ships that have entered the icy waters. It reveals that the continent is connected to all regions of the globe via an extensive network of shipping pathways. Fishing, tourism, research, and supply ships are exposing the world’s iciest continent to invasive, non-native species that threaten the stability of its undisturbed environment.

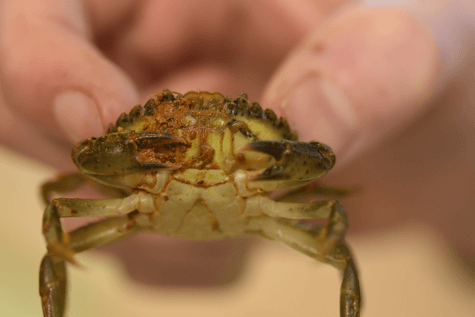

To understand where the species came from, the team identified 1,581 ports with links to Antarctica, where they believe the invasive species could have come from. The species – including mussels, barnacles, crabs, and algae – attach themselves to the hulls of ships, in a process known as biofouling.

“Invasive, non-native species are one of the biggest threats to Antarctica’s biodiversity – its native species have been isolated for the last 15-30 million years,” says senior author professor David Aldridge, from the department of zoology, in a statement. “They may also have economic impacts, via the disruption of fisheries.”

‘New form of predation that Antarctic animals have never encountered before

The scientists express particular concern about the movement of species from pole to pole. Aldridge explains that the species are already cold-adapted and may make their journey on tourist or research ships that spend the summer in the Arctic, before traveling across the Atlantic ocean to make way for the Antarctic summer season.

“The species that grow on the hull of a ship are determined by where it has been. We found that fishing boats operating in Antarctic waters visit quite a restricted network of ports, but the tourist and supply ships travel across the world,” says first author Arlie McCarthy, a researcher in the university’s department of zoology and the British Antarctic Survey.

The team discovered that research vessels stayed at Antarctic ports for longer periods of time than tourism ships, while fishing and supply ships stayed for even longer. Previous research into this area shows that longer stays increase the likelihood of non-invasive species being introduced to their new homes.

Due to its remote, isolated location, there are many species that Antarctic wildlife can’t tolerate. Mussels, for example, grow on the sides of ships and never come face to face with Arctic competitors because there are none. Shallow-water crabs would introduce a new form of predation that Antarctic animals have never encountered before.

“We were surprised to find that Antarctica is much more globally connected than was previously thought. Our results show that biosecurity measures need to be implemented at a wider range of locations than they currently are,” says McCarthy. “There are strict regulations in place for preventing non-native species getting into Antarctica, but the success of these relies on having the information to inform management decisions.

“We hope our findings will improve the ability to detect invasive species before they become a problem,” she adds.

Better biosecurity measures needed

The study combined port call data with raw satellite observations of ship activity south of -60 degrees latitude, over the course of four years, from 2014 to 2018. By studying this data, the team found that vessels most frequently sailed between Antarctica and ports in southern South America, Northern Europe, and the western Pacific Ocean.

The Southern Ocean that surrounds Antarctica, is the most isolated marine environment on the planet. It supports a unique mix of plant and animal life and it is the only global marine region without any known invasive species, so protecting it from harm is the researchers’ top priority.

The scientists warn that large krill fisheries in the southern oceans could also be disrupted by invasive species hitchhiking on the back of ships. Small fry fish is a major component of the fish food used in the global aquaculture industry, and krill oil is sold widely as a dietary supplement.

“Biosecurity measures to protect Antarctica, such as cleaning ships’ hulls, are currently focused on a small group of recognized ‘gateway ports,'” says professor Lloyd Peck, a researcher at the British Antarctic Survey. “With these new findings, we call for improved biosecurity protocols and environmental protection measures to protect Antarctic waters from non-native species, particularly as ocean temperatures continue to rise due to climate change.”

The findings are published in the journal PNAS.

Report by South West News Service writer Georgia Lambert.