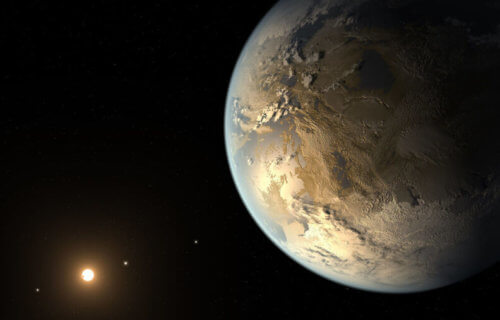

PULLMAN, Wash. – When you consider the infinite size of the universe, there’s no question Earth is special. Our planet sits in that perfect little zone, around a perfectly warm enough sun, which makes life possible. A new study however is giving Earthlings a dose of cosmic reality. Astronomers say Earth isn’t so perfect after all and they’ve found two dozen planets which may be even more suitable for life than our home.

Washington State University scientist Dirk Schulze-Makuch says our galaxy is home to planets which potentially fall into the category of “superhabitable.” Those Earth-like exoplanets include ones which are older, larger, warmer, and wetter than the Earth. Superhabitable planets which circle around their stars slower could also help life to thrive more easily than it does here.

The study picked out the top 24 interstellar contenders, all of which are over 100 light-years away from our solar system. Schulze-Makuch says the research could help scientists focus their search for life before future space telescopes are launched. NASA’s James Web Space Telescope, the LUVIOR space observatory, and the European Space Agency’s PLATO space telescope are the most notable projects planned for launch in the next 20 years.

“With the next space telescopes coming up, we will get more information, so it is important to select some targets,” the professor at WSU and the Technical University in Berlin explains in media release. “We have to focus on certain planets that have the most promising conditions for complex life. However, we have to be careful to not get stuck looking for a second Earth because there could be planets that might be more suitable for life than ours.”

What makes a planet better than Earth?

Schulze-Makuch, René Heller of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, and Edward Guinan of Villanova University teamed up to figure out what makes an exoplanet more habitable than Earth. Their study sorts through 4,500 known exoplanets which telescopes have discovered outside the solar system.

Although exoplanets are Earth-like, that doesn’t mean all of them have life like Earth. Scientists explain that these planets are special because they all share the conditions which make life possible and sustainable.

One of the biggest requirements is that the contenders sit inside the habitable zone of their solar system. This means they are close enough to their star to allow liquid water to form. The study finds the lifespan of that sun also helps keep the window for life open longer. While our sun (a G-type star) will last for less than 10 billion years, researchers find K-type dwarf stars last for between 20 and 70 billion years. K-type stars are cooler and dimmer, but they allow their planets more time to develop complex lifeforms.

As Earth has shown, it can take a very long time for life to spring into existence. On this planet, it took four billion years for life to arrive and the study finds Earth may not even have reached its “sweet spot” for life yet. This may come when our planet is between five and eight billion years-old.

Size also makes a big difference. Researchers say a planet 10-percent bigger than the Earth will give life more habitable land to roam on. An exoplanet 1.5 times the size of our home would likely have a core that stays warmer much longer and have a higher gravity which holds its atmosphere longer too.

Above all, water is the key. Study authors say planets that can provide more moisture, clouds, humidity, and a slightly warmer ground temperature than Earth would fall into the superhabitable group.

So who makes the final cut?

Of the 24 in the study’s final list, Schulze-Makuch says none actually meet every single benchmark for superhabitable status. Despite this, one of the worlds meets four of the requirements and that could possibly make it an even nicer place to live than Earth.

“It’s sometimes difficult to convey this principle of superhabitable planets because we think we have the best planet,” adds Schulze-Makuch. “We have a great number of complex and diverse lifeforms, and many that can survive in extreme environments. It is good to have adaptable life, but that doesn’t mean that we have the best of everything.”

The study appears in the journal Astrobiology.