MEDFORD, Mass. — A whole new wardrobe of smart clothing will be able to measure athletic performance and even enhance virtual reality games. The high-tech apparel could also monitor worker or driver fatigue, help with physical therapy and improve computer generated imagery in cinematography.

Measuring movement in real time, the groundbreaking design uses flexible thread sensors that can be attached to skin. This could be a game changer on the athletic field, where thin tattoo-like patches could track athletes’ health and performance. On the road, a thread sensor patch could also alert to truck driver fatigue, monitoring the head movements of someone about to nod off.

The discovery adds to the growing number of thread-based sensory developed by engineers at Tufts University in Massachusetts, USA.

“This is a promising demonstration of how we could make sensors that monitor our health, performance, and environment in a non-intrusive way,” says study lead author Yiwen Jiang, an undergraduate at the private research university, in a media release. “While algorithms will need to be specialized for each location on the body, the proof of principle demonstrates that thread sensors could be used to measure movement in other limbs. The skin patches or even form-fitting clothing containing the threads could be used to track movement in settings where the measurements are most relevant, such as in the field, the workplace, or a classroom.”

Futuristic threads can be applied through sensors woven into clothes, patches

By placing thin tattoo-like patches on different joints, an athlete could carry motion sensors to detect their physical movement and form. While thread-based sweat sensors, described in earlier work by the Tufts team, could also track their electrolytes, lactate and other biological markers of performance in sweat.

“If we can take this technology further, there could be a wide range of applications in healthcare as well,” says Jiang. “For example, those researching Parkinson’s disease and other neuromuscular diseases could also track movements of subjects in their normal settings and daily lives to gather data on their condition and the effectiveness of treatments.”

The sensor technology can be woven into textiles, measuring gases and chemicals in the environment or metabolites in sweat. Measuring neck movement, the sensors provide data on the direction, rotation angle and displacement of the head.

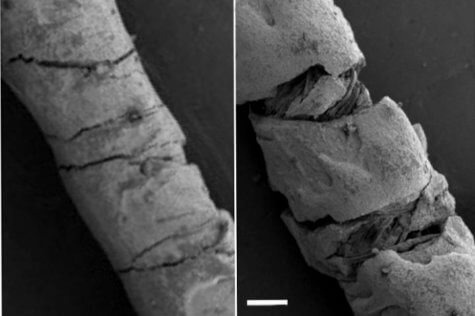

In their experiments, the researchers placed two threads in an “X” pattern on the back of a subject’s neck. Coated with a carbon-based ink, the sensors detect movement when the threads bend, creating strain that changes the way they conduct electricity. When the subject performed a series of head movements, the wires sent signals to a small Bluetooth module which then sent data wirelessly to a computer or smartphone for analysis.

These signals were then translated into head movements in real time, with 93 percent accuracy.

“In this way, the sensors and processor track motion without interference from wires, bulky devices, or limiting conditions such as the use of cameras, or confinement to a room or lab space,” says Jiang. “The fact that a camera is not needed provides for additional privacy.”

‘Remarkable achievement’

Other types of wearable motion sensor designs include 3-axis gyroscopes, accelerometers and magnetometers to detect a person’s movement in relation to their surroundings. Those sensors measure how the body accelerates, rotates or moves up and down and tend to be bulkier and more inconvenient.

In order for other systems to measure head movement, one sensor must be placed on the forehead and another on the neck. This can interfere with the person’s free movement or simply the convenience of not being conscious of being measured.

“The objective in creating thread-based sensors is to make them ‘disappear’ as far as the person wearing them is concerned. Creating a coated thread capable of measuring movement is a remarkable achievement, made even more notable by the fact that Yiwen developed this invention as an undergraduate,” explains co-author Professor Sameer Sonkusale, also of Tufts University. “We look forward to refining the technology and exploring its many possibilities.”

Researchers say more work needs to be done to improve the sensors’ scope and precision. This could include gathering data from a larger array of threads arranged in a pattern, and developing algorithms that improve the quantification of articulated movement.

The findings are published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Report by SWNS writer Laura Sharman.