WASHINGTON — In a nod to pop culture that bridges the gap between science and kids of all ages, a team of scientists has given a name to a prehistoric fossil that’s straight out of our childhoods. The star of the show? None other than Kermit the Frog.

That’s right. The beloved Muppet character now shares his name with a 270-million-year-old proto-amphibian ancestor, whose fossilized skull was uncovered in the halls of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

The team identified the fossil as a new species of early amphibian, which they honored with the name Kermitops gratus. The researchers expressed that choosing to name the discovery after the celebrated frog, created by puppeteer Jim Henson in 1955, was an opportunity to spark public interest in scientific discoveries stemming from museum collections.

“Using the name Kermit has significant implications for how we can bridge the science that is done by paleontologists in museums to the general public,” says Calvin So, the lead author of the study and a doctoral candidate at George Washington University, in a media release. “Because this animal is a distant relative of today’s amphibians, and Kermit is a modern-day amphibian icon, it was the perfect name for it.”

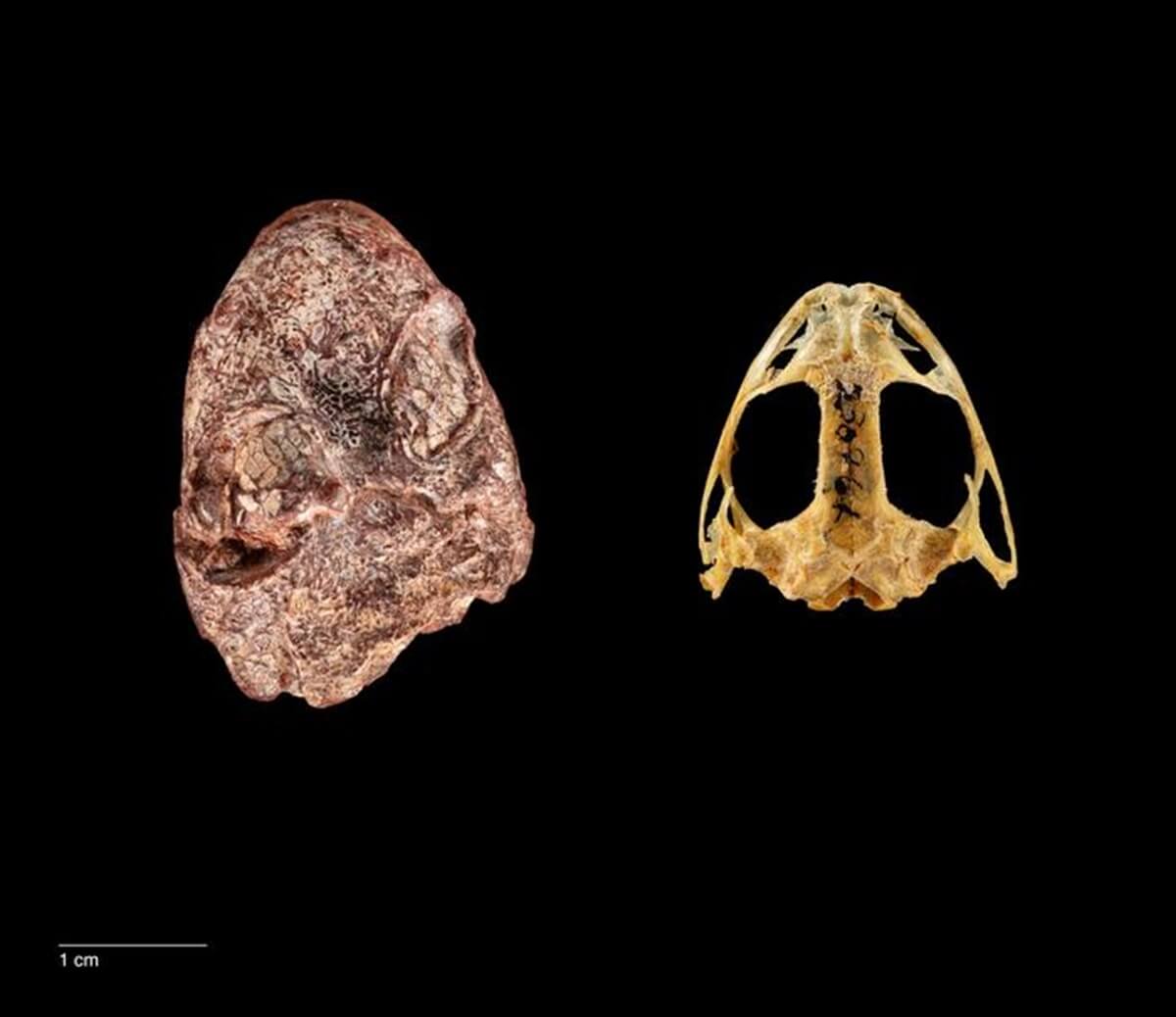

The fossilized skull, just over an inch long with prominent, oval-shaped eye sockets, was originally found by the late paleontologist Nicholas Hotton III. Hotton, a curator in the museum’s paleobiology department for nearly four decades, dedicated years to extracting fossils from the Red Beds rock formations in Texas.

These rust-hued rocks, dating back to the early Permian period over 270 million years ago, hold the fossilized remains of ancient reptiles, amphibians, and sail-backed synapsids, precursors to today’s mammals. Amidst numerous finds, a small proto-amphibian skull discovered in the Clear Fork Formation in 1984 was among the treasures. It was stored within the Smithsonian’s National Fossil Collection, where it remained unnoticed for decades.

In 2021, Arjan Mann, a postdoctoral paleontologist and mentor to Mr. So, encountered this specimen while examining Hotton’s collection of Texas fossils. A certain fossil, labeled as an early amphibian, caught his attention due to its exceptional preservation.

Together, Mann and So sought to classify this prehistoric entity. Their analysis revealed a unique amalgamation of characteristics, setting it apart from the skulls of older tetrapods — ancient forebears of amphibians and other four-legged vertebrates. The researchers point out differences in the skull, such as a shorter area behind the eyes compared to the elongated, curved snout.

“These skull proportions helped the animal, which likely resembled a stout salamander, snap up tiny grub-like insects, ” adds Mann.

The fossil was recognized as a temnospondyl, part of a broad group of early amphibian relatives. Its distinct features led the researchers to assign it to a new genus, Kermitops, inspired by its cartoonish, wide-eyed appearance, combining “Kermit” and the Greek suffix “-ops,” meaning face.

The species name, gratus, was chosen to express appreciation for Hotton and his colleagues’ initial discovery. However, the significance of Kermitops extends beyond its puppet-inspired name. The early amphibian fossil record is notably incomplete, complicating efforts to trace the origins of frogs, salamanders, and related species.

“This is an active area of research that a lot more paleontologists need to dive back into,” adds Dr. Mann. “Paleontology is always more than just dinosaurs, and there are lots of cool evolutionary stories and mysteries still waiting to be answered. We just need to keep looking.”

The study is published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.

SWNS writer Stephen Beech contributed to this report.