SOLNA, Sweden — It’s been called the “granddaddy of addictive puzzles.” But a new study finds the popular video game Tetris may have applications far beyond leisure.

Researchers at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden have found that trauma victims who played Tetris within the first six hours of entering a hospital emergency room were less likely to suffer flashbacks than those that were exposed to other mental treatments. Moreover, their flashbacks were less frequent and tended to disappear more quickly.

The Institute’s study featured 71 adults who had suffered motor vehicle accidents and ended up in the emergency department at John Radcliffe Hospital at Oxford University in London. About half of the patients played Tetris on a Nintendo DS at twenty-minute stretches. The other half were asked to journal, send texts, read or fill out crosswords. The patients who played Tetris reported having an average of about nine intrusive memories — 62 percent less than the average number of distressing memories experienced by non-players.

“Our hypothesis was that after a trauma, patients would have fewer intrusive memories if they got to play Tetris as part of a short behavioural intervention while waiting in the hospital Emergency Department,” says study director Emily Holmes, professor of psychology at the institute’s Department of Clinical Neuroscience in a news release. “Since the game is visually demanding, we wanted to see if it could prevent the intrusive aspects of the traumatic memories from becoming established i.e. by disrupting a process known as memory consolidation.”

“Anyone can experience trauma,” Holmes added. “It would make a huge difference to a great many people if we could create simple behavioural psychological interventions using computer games to prevent post-traumatic suffering and spare them these grueling intrusive memories.”

Holmes has studied the Tetris-trauma connection before – but never with actual trauma victims. In 2010, her research team had student volunteers watch films with images of gruesome violence. The group that played Tetris experienced a reduction in trauma memories, while a control group that played a separate game, Pub Quiz, actually saw their flashbacks increase.

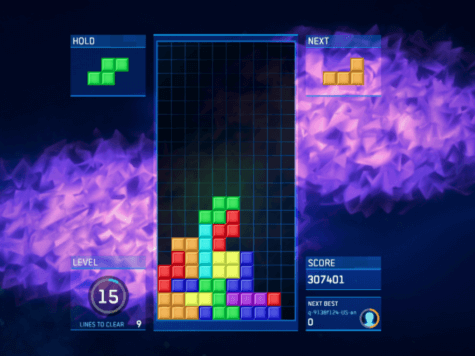

It’s not that Tetris actually wipes out the memories of trauma. Instead the game, which demands that users try to position rapidly falling puzzle blocks in a succession of horizontal rows, demands intense mental and visual concentration. The brain only has so much room for visual memory. In effect, Tetris crowds out the space for flashbacks to appear, and through repetitious playing, substitutes equally compelling imagery.

“Tetris is a highly absorbing visual game,” Holmes told the Washington Post. “It’s all symbols, no text. In your mind’s eye, you see the blocks coming down. It requires visual attention and your working memory as you’re trying really hard to position those blocks.”

Holmes hopes to test Tetris with other patient groups, including victims of physical assault, rape and war. Soldiers and refugees, she notes, are especially likely to become chronic PTSD sufferers. Though often far beyond the early trauma stage, these group might still benefit from Tetris or from similar puzzle games just now entering the video market, she argues.

The results of Holmes’ latest study were published in the March 2017 issue of the journal Molecular Psychiatry. Researchers at Oxford, the University of East Anglia and Cambridge University in Britain and at Ruhr University in Germany were also involved in carrying out the study.