MEDFORD, Mass. — “I had the strangest dream last night!” If this is something you’ve found yourself saying more frequently during the coronavirus pandemic, scientists have an explanation as to why. It turns out that weird dreams may be key to help people through difficult times in life.

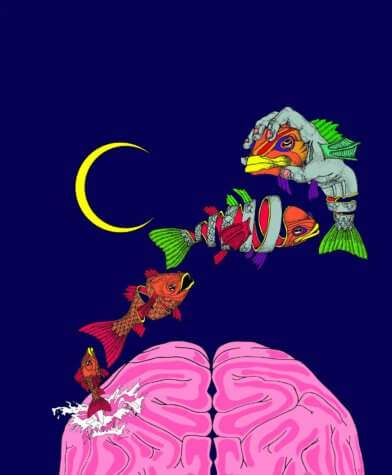

Researchers from Tufts University say bizarre visions while we sleep actually help us cope with the stresses and strains of life when we are awake. The unusual dreams make the world seem less simplistic — and more well-rounded.

“It is their very strangeness that gives them their biological function,” explains study lead author Dr Erik Hoel, a research assistant professor of neuroscience at Tufts University, in a statement.

The discovery adds to growing evidence we should embrace nightmares, which have increased during the health crisis. They are believed to be sub-consciously dampening fears about lockdowns and catching COVID-19. The vivid images enable our brains to generalize day-to-day events better, the study found.

“There is obviously an incredible number of theories of why we dream,” says Hoel. “But I wanted to bring to attention a theory of dreams that takes dreaming itself very seriously — that says the experience of dreams is why you are dreaming.”

Described in the journal Patterns, he has named it the “overfitted brain hypothesis.” It is similar to artificial intelligence techniques used to train deep neural networks. They introduce a regularization method called “dropout,” in which extra data is introduced to help computers identify the important stuff.

Our brain, like computers, also become too familiar with the “training set” of our everyday lives. To counteract the familiarity, it creates a crazy image of the world in dreams, the mind’s version of dropout.

“The original inspiration for deep neural networks was the brain,” explains Hoel. Using them to represent the overfitted brain hypothesis was a natural connection. “If you look at the techniques that people use in regularization of deep learning, it is often the case they bear some striking similarities to dreams,” he says.

It has already been shown the best way to prompt dreams about real life is to repetitively perform a novel task. When you over-train, the phenomenon is triggered, and your brain attempts to generalize by creating dreams. Hoel argues it could be proven this is really why we dream, with well-designed behavioral tests and sleep deprivation.

‘Dreams keep you from becoming too fitted to the model of the world’

Another area he wants to explore is the idea of “artificial dreams.” The overfitted brain hypothesis was inspired by fictitious films and books. Outside stimuli, including TV shows, may act as dream “substitutions.”

They could even delay the cognitive effects of sleep deprivation by emphasizing their dream-like nature by virtual reality technology. You can simply turn off learning in artificial neural networks, but you can’t do that with the brain, says Hoel. Brains are always learning new things, and that is where the overfitted brain hypothesis comes in to help.

“Life is boring sometimes. Dreams are there to keep you from becoming too fitted to the model of the world,” he adds.

Earlier this year, a study of more than 500 doctors and nurses in the Chinese city of Wuhan — the epicenter of the pandemic — found over a quarter were having frequent nightmares. They also rose among citizens during national lockdowns, with young people, women and those suffering anxiety or depression most prone.

Vivid dreams help us to process the emotions of the previous day, say psychologists. Understanding why bad dreams become nightmares is helping to treat victims of trauma.

Experts are beginning to unravel the links between dreams, mental disorders and their importance in keeping us emotionally stable. During sleep, we organize and file away memories of the previous day and give our older memories a bit of a dust-off and reshuffle. It is in the REM (Rapid Eye Movement) stage just before we wake or as we drop off we store our most powerful recollections. These emotionally charged memories then become the subject of our dreams.

Previous research has found a bad dream helps in waking life.

“‘Sleep to forget, sleep to remember’ suggests REM sleep strengthens emotional memories, safely storing them away,” says Hoel. “It also helps to tone down our subsequent reactions. For example, if your boss shouts at you and later that night you dream about it, the next time you see them you will feel less upset or angry. We are most likely to remember the dreams we have just before awaking or as we dip into sleep.”

SWNS writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.