NEW YORK — For anyone that has undergone a life-saving transplant, they know how important organ donation can be. Now, a new study finds stem cells taken from deceased patients may also help in creating a cure for blindness. Researchers say retina cells from a corpse continue to survive after being transplanted into the eyes of monkeys.

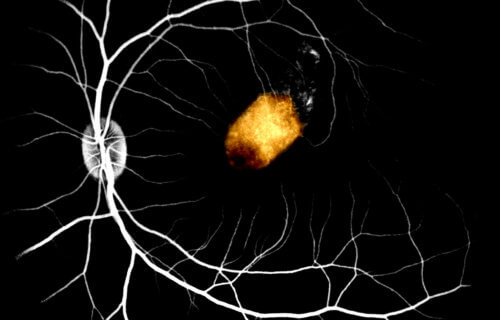

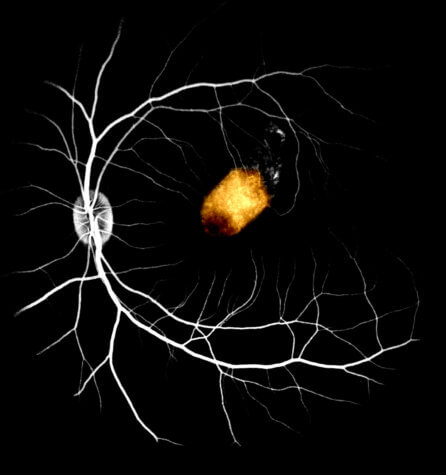

Retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), a layer of cells in the eyes, transports nutrients and waste products to and from the retina. These cells also act as a barrier and help regulate light receptors, all of which are “essential” for normal vision.

RPE dysfunction is a leading cause of blindness, including causing disorders like macular degeneration, which affects around 200 million people worldwide. Now, for the first time, scientists have successfully produced retina cells in monkeys using human stem cells.

“We have demonstrated human cadaver donor-derived RPE at least partially replaces function in the macula of a non-human primate,” reports co-author Dr. Timothy Blenkinsop at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in a media release. “Human cadaver donor-derived cells can be safely transplanted underneath the retina and replace host function, and therefore may be a promising source for rescuing vision in patients with retina diseases.”

Treating blindness without side-effects

Researchers transplanted stem cells from the eyes of donated bodies under the monkey’s macula, the central part of the retina. Following surgery, the transplanted patches remained stable for at least three months without any serious side-effects.

Study authors add that RPE created by the human stem cells partially took over from the old retina cells. Blenkinsop adds that they could also successfully support the eye’s light receptors without causing retinal scarring.

These unique cells could serve as an “unlimited resource” of human RPE, which may restore sight for millions of people around the world. The scientists caution that they will need to conduct more research to see how the procedure works with human transplant patients. Human trials are still a long way off.

“The results of this study suggest human adult donor RPE is safe to transplant, strengthening the argument for human clinical trials for treating retina disease,” Dr. Blenkinsop concludes.

The findings appear in the journal Stem Cell Reports.

SWNS writer Tom Campbell contributed to this report.